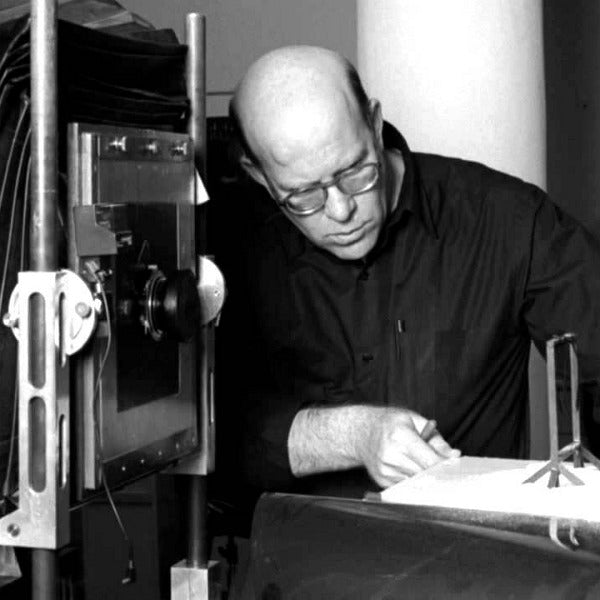

Photographer David Levinthal

A soldier, a cowboy, a blonde.

For many Americans, these were their toys. Made of metal or wood or plastic, these mainstays of American pre-adolescent play were the archetypal representations of war, myth, and beauty on which much of the American child’s imagination was built. For at least one, however, they became the foundation for lifelong artistic exploration and expression.

The photographer David Levinthal recalls a instance when he was playing with toys. One year, over winter break, he decided to recreate a scene from World War II on his bedroom floor. He found a plastic bridge and made the river water out of blue craft paper. He placed his soldiers carefully in the scene, and with some matches and aluminum foil, he set the bridge alight. The fire melted some of the linoleum floor underneath. When his mother found out she remarked, “I never liked that floor anyway.” His equally accommodating father said, “David’s happy, that’s the most important thing.”

This was not an episode from an unruly childhood, but from Levinthal’s time at Yale graduate school, where he studied photography. The fire on the linoleum floor was the end point in a series of photographic experiments involving toys. He began by attempting to photograph each room in a metal Marx dollhouse but found the tin walls too reflective. So he shifted his attention and bought some toy soldiers that he photographed a series in which they appeared to be coming out of their own wrapping. Levinthal started making sets for his soldiers. First he borrowed his youngest brother’s wooden block city, then he bought trees and poles with which to embellish the soldiers’ environment even more. Eventually, his play culminated in the fire on his bedroom floor and a preoccupation that would define his artistic career.

Photo: Courtesy of the David Levinthal Studio

Levinthal was born in San Francisco, California. His undergraduate studies were at Stanford University, where he initially planned to major in political science with the intention to become a constitutional lawyer. At Stanford, there was something called the “Free University” where almost anyone could teach non-credit classes. These classes included one called “LSD and Tantric Yoga”. Levinthal decided to take a (perhaps less provocative) photography class taught at the Free University by a young man with long hair called Dwight. Levinthal thought Dwight epitomized “cool” and vaguely hoped that by learning photography from Dwight he, too, might become cool.

Stanford did not offer a for-credit photography course at the time, so Levinthal found other ways to pursue his interest. He took classes at the University of California photography program with Ruth Bernhard. He took pictures for the Stanford Daily News. Using his press pass, he was able to make his way past police lines during 1967’s Oakland draft protests against the Vietnam War and photograph the events. He became part of the photography scene in San Francisco, wrote film reviews, made Super 8 movies, and finished his time at Stanford with a degree in studio art.

After Stanford, Levinthal chose Yale Graduate School to study photography, mainly because Walker Evans, the American photographer known for his depictions of the Great Depression, taught there. It was at Yale that he first began taking pictures of toys. His first germ was wanting to recreate images from old pulp magazines from the 50s like the Police Gazette. He reasoned a Barbie doll could stand in for a woman and the black bars over her eyes used to “protect” her identity could be replicated by black tape. From here he became more ambitious leading to his prolific winter break. He returned with 400 or 500 prints of war made with toys. He had used Kodalith paper which is black and white photographic paper that produces very dense blacks. Levinthal found that if he got the paper wet he could create a sepia tone that was similar to old, grainy photographs from documentaries.

Photo: Courtesy of the David Levinthal Studio

In his final years at Yale, Levinthal sent out his portfolio to many universities, looking for teaching positions. One was accidentally returned with Walker Evans’ recommendation inside. Levinthal was touched by the short letter from his old teacher where he described his work as “notable for the unusual combination of soundness and originality.” Levinthal hadn’t realised his teacher had thought so highly of his unorthodox work. He holds onto that letter to this day. After graduation, Levinthal shared a house in New Haven (Connecticut) with fellow classmate Jerry Thompson. During this time, Thompson printed for Evans. Evans would often stay the night at their house when he wasn’t feeling strong enough to make his way home to Old Lyme about thirty miles away.

Levinthal’s work with Kodalith paper and toy soldiers lead directly into his first major work. At Yale, Levinthal became friends with fellow graduate student Garry Trudeau, the creator of the comic strip Doonesbury. Trudeau was earning a master’s in graphic design, specializing in German and Nazi graphics. Part of his work included a fictional biography of a Luftwaffe pilot. Trudeau’s publisher suggested they collaborate on a book together. The result, which would take three and a half years (two and a half years longer than their contract indicated), was Hitler Moves East. It tells the story of the German army’s ill-fated Russian campaign with first-hand quotes, short passages, and Levinthal’s evocative photography.

There’s one photograph in the book of two soldiers in the ruins of a building. A lot of the image is in darkness. There’s a smear in the foreground as if the photograph has been worn out. The action is mostly out of focus, with clumps of clarity occasionally concentrating into meaning. Two pillars in the background, rubble in the foreground, and two men. In the center, one of the men is a soldier, with his rifle to his shoulder, aiming at some unseen threat through a hole in a collapsing wall. On the left of the picture, there’s a second soldier moving forward. A great light is coming in, fading him into silhouette, as if the camera, in the action of the battle, had been dragged quickly and caught the sun.

In his photographs, Levinthal creates the harrows of war from toy figures and little sets. The wheat fields are grass seed and the snow is made of flour. The book became an unclassifiable, underground classic. People didn’t know what to make of his photographs. Levinthal remembers meeting a woman at an event for the book, and upon learning he was the photographer, said “You’re awfully young to have taken these photos in World War II.” Much of the power of his images comes from his ability to create a sense of motion where there is none and create what seems real from what to the naked eye would appear obviously false.

Levinthal says, “there’s less to my images than meets the eye.” His set up, he claims, is very simple. He sets the camera up very close and uses a depth of field that is incredibly narrow. This causes the image to turn soft and blurry, giving the illusion of movement. For many years, Levinthal used a Polaroid camera which allowed him to create photos within minutes. Since so much of his work relies on making tiny adjustments to a diorama or set, which, at the scale he works at, entirely remakes the image, it was important to have feedback quickly. Today he uses a Hasselblad camera, having reluctantly made the switch to digital.

Levinthal’s current home in Manhattan’s Flatiron District used to be his studio. It’s an open loft space partitioned with movable, gallery walls. As you enter, a large display of amalgams of pop culture characters fill the entrance: Astroboy, Mickey Mouse, a Star Wars stormtrooper -- all with crosses over their eyes. These are the design of KAWS a.k.a Brian Donnelly, an artist who also works with toys and is a friend of Levinthal’s. Stuck to the ceiling, there are three gold balloons spelling out D-A-D slowly deflating. Opposite the living room space is a wall-sized photograph by Levinthal. It depicts a helicopter in shadow against the bursting orange glow of perhaps a sunset or an explosion glittering off a sea. The image summons a memory of the Vietnam War seen through the prism of cinema.

Levinthal’s work is often based on sifting through his childhood memory and nostalgia and reworking ubiquitous images of popular culture. The photograph of the helicopter on the wall of his house owes as much to a pop cultural idea of the Vietnam War from films like Apocalypse Now as it does images of the actual war. Levinthal decided to shoot pictures for his IED series, depicting the Iraq War, using digital film because “that’s how it’s being seen” in the news. The root of his inspiration may be more opaque and personal. Perhaps the film noir quality to his very early black and white work Bad Barbie was borne out of a memory of watching The Asphalt Jungle as a child with a grilled cheese and tomato soup.

His series’ Desire and XXX are informed by the “forbidden iconography” at the back of the video store where the Playboys and the Penthouses were kept. These works depict figurines of naked women in various pin up poses, again shot to obscure their toy-like reality. For some, these are his most uncomfortable images. Levinthal recalls being interviewed in Paris for his XXX Series in 2000 where he was asked which pictures were of real women and which were of toys. The way Levinthal can frame a toy to look in motion and like the real thing often unsettles, and continues to provoke disbelief. The knowledge that the toy is not real but that it appears so creates a powerful dissonance.

Though, some of Levinthal’s work does not attempt to mingle the real with the unreal. His Blackface series photographs blackface memorabilia with no sets, against a black background, and no attempt is made to create movement or dissemble. While the images in this series can seem simple, Levinthal considers it his “most subtle work.” He is not just documenting, with his focus and his cropping, he is “interpreting and transforming.”

The subject that Levinthal keeps coming back to, however, is cowboys. As a child, Levinthal had a set of cowboy figurines that were hand-painted in Germany. He recalls a period of his life when he insisted on wearing his Red Ryder cowboy gloves in order to join his mother to run errands. He was obsessed with Cowboys and Indians. Today he is still obsessed with Cowboys and Indians. He has now made five series on the Wild West over the course of his career: 1986 - 1988; 1987 - 1989; 1998; 2002; 2012. In each, Levinthal forages for a different understanding. One series is epic. There’s a picture of an American Indian in shadow aiming a bow and arrow on a rearing horse into the red sky. Another series is shot in sepia and suggests a historical reality that is perhaps equally mythologized. For all the changes in American culture in recent years, the Wild West remains a potent and diverse myth and a touchstone for interpreting American values.

A toy allows a child to imagine. But a toy is not an empty totem. Each toy is a bundle already carrying a culture’s myths and ideas. The work of the photographer David Levinthal asks us to question and explore within, beneath, and outside the seemingly simple world of play.

There is a major career Retrospective of Levinthal’s work appropriately titled War, Myth, Desire at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, running until the end of 2018.

Photographs from New York Makers' visit to David Levinthal's War, Myth, Desire at the George Eastman Museum.

Leave a comment