During times of crisis — war, famine, disease — does art matter?

An easy and obvious response to that question would be that, no, making and appreciating art can’t possibly be as important as life itself. But a different answer, and perhaps a more thoughtful one, provided by artist Robert Zakanitch, is that art is life. And without it, where are we as a collective culture and as individual human beings?

“What we’re going through right now with the coronavirus reminds me of what happened after 9/11,” Zakanitch says. “Everyone is grieving, and, for a moment, art seems trivial. But we need the caring and beauty that is found in the making of all of the arts. It is in an intrinsic part of their existence. Everything we do, every move we make, from the moment we open our eyes in the morning, is touched by art. We sleep in a bed, we put on clothing, we wander out to the kitchen and make coffee. Every single object was created to be used, to be functional, but also please. Nothing happens without creativity and art. Nothing comes from nothing.”

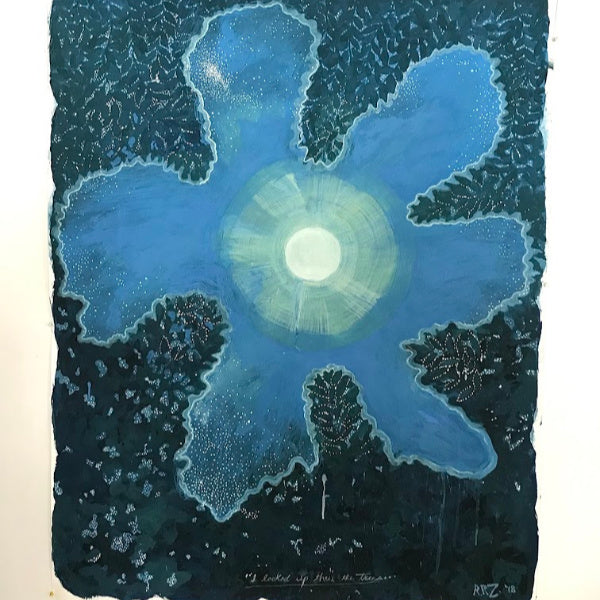

Zakanitch's Yonkers studio

In the 1970s, Zakanitch aided in launching an artistic movement — Pattern and Decoration, or P&D — and built an entire career on the notion that art infused the everyday. From paintings on canvas, to music, to literature, to architecture and industrial hardware, art and decoration shapes our paradigms. The P&D movement was created in response to what Zakanitch and other practitioners believed was a necessary and stern rebuke to the patriarchal, empirical themes that dominated Western art from the Renaissance onward. Zakanitch and others, including Joyce Kozloff, Robert Kushner, Takako Yamaguchi, and Miriam Schapiro, sought inspiration for their work in the natural world, and outside of the United States, in Spain, North Africa, Mexico, and through the ancient artistic cultures of Japan, Turkey, and India.

We sat down with Zakanitch to learn more about the decades-long conversation he has been having with fellow artists and the culture at large through his iconic, large-scale paintings, many of which are collected in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Whitney Museum of American Art, and are also included in the P&D retrospective “With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972-1985,” showing at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles through May 11th and then headed to Bard College’s Hessel Museum of Art in June.

Press play to watch an interview with Robert Zakanitch at the Hudson River Museum. Video courtesy of Donald Rosenfeld.

New York Makers: You were born in 1935 in Elizabeth, New Jersey to a mechanic father and a homemaker mother who worked in a factory. How did you begin your work as an artist?

Robert Zakanitch: Art has always been part of my life. I always saw beauty in the everyday object. I wasn’t a great student. After high school, I eventually landed at the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Art because that’s what moved me. While I was there, I studied with Ben Cunningham, an Op-Art practitioner and Hans Beckman, a German expressionist. It changed my world, it just opened everything up for me.

NYM: You were successful early on, showing at art galleries around the U.S. and Europe and teaching art at colleges around the country. You married [the late] Patsy Norvell, a sculptor, and you had a daughter, now grown. Why and when did you decide to launch an art movement, and can you describe the basics of the Pattern and Decoration movement for those who are unfamiliar?

RZ: It really got going in the 70s when my career was already established, and so were those of many of the people involved. We knew what we wanted to see and what we were seeing in the art world. The movement embraces forms that were classically regarded as feminine, ornamental, or craft-based, and didn’t merit serious consideration. They were thought of, essentially, as inferior. We rejected that completely and, instead, embraced the notion that ‘more is more’ in every way. That was expressed through our conscientiously empathetic and humanistic approach to creating art. It also contributed to our perception of what art is and could be. We wove floral and arabesque patterns into our work, creating colorful and lively designs, working across mediums, and generally rejecting the aesthetics of modernism and minimalism. We launched it because we thought it was important for us as individuals, and also as a culture, to bring us to a more humane, empathetic place.

NYM: When you were beginning this movement, did you think of it as a movement, as something that would change art?

RZ: We did. We would meet and talk about art, about the importance of shifting the culture. It was very much on our minds. What we didn’t know at the time, was that it would succeed. We were hitting the soft spots, the tender spots; we were objecting to war, to what had become institutionalized cruelty. Art was so intellectualized. I remember growing up and starting out as an artist and hearing that ‘if your audience gets it, then it isn’t good.’ Well, I think that’s crazy. I want to paint for my audience. I want art to be about being human, about beauty and even for fun. We were all fighting to get those things back, to push back on relentless deconstruction of all of the arts and the stripping down to nothingness. And we did change not only the art world, but also mainstream opinion. Now rugs, plates, even refrigerators or stoves are seen by people as potential expressions of artistry.

NYM: Of all of your work over several decades, do you have one that you’re most proud of?

RZ: Every piece of art I’m working on at the time seems essential. I invest everything I have in it. But, one of my all-time favorites is “Big Bungalow Suite.” It’s on five canvases that are 11 feet high and 30 feet long, and it elevates subject matter that for so long was considered ‘just decorative.’ It’s a deep, intricate study of everything that influenced me in my life and career. It includes in-depth examinations of floral rugs and painted plates, of patterned floors. But in the end, every piece of art I see as a part of the whole. My goal is to always keep growing, stay fresh and positive. Making art and seeing art to me, is about healing. Art should elate you, give you a moment of joy, make you feel compassion and good about yourself.

NYM: What would you tell artists working now?

RZ: I don’t know if I’d dare to give an artist advice. An artist has to find his or her own way. But I like what I’m seeing. Art doesn’t have to be a reflection of what’s happening in the world; but, instead, it can be used to direct the culture toward compassion, empathy, and humaneness. Which we need now, more than ever.

We do. And speaking to Zakanitch was a powerful reminder to stop and smell —and see— the roses, wherever we may find them, especially now.

Leave a comment