The dreary days of winter are, in my opinion, good for precisely two things: reading and daydreaming — and the two converge if you've picked the right material.

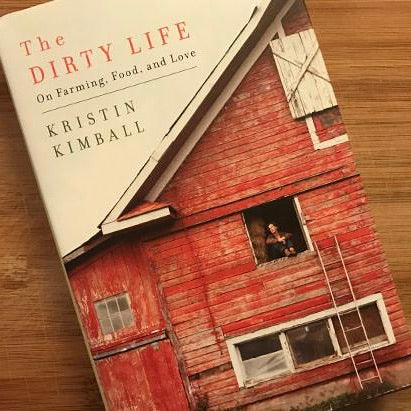

This month I found myself unconsciously reaching for two memoirs that coalesce at that intersection: Kristin Kimball's The Dirty Life: On Farm, Food and Love and Josh Kilmer-Purcell's The Bucolic Plague: How Two Manhattanites Became Gentleman Farmers. Though I first read these books years ago they remain vivid in my memory and are a joy to revisit (and I have gifted copies to many, many friends). Set respectively in New York's Essex and Schoharie counties, they also offer visceral accounts of winter in the Empire State that promptly put my cold weather complaints in perspective.

Before her "dirty life" began, Kristin Kimball was a journalist for publications like "Vogue," she lived an enviably chic life in Manhattan and had, as she states in her book: "been all over the world as a travel writer [and] done all the things that people spend their money and their vacation days to do." She embarked on an entirely new chapter after she fell in love with a farmer and they were granted land in New York's northeastern corner on which to cultivate the farm of their dreams. (Spoiler alert: they now successfully operate Essex Farm and a CSA of the produce they grow.)

While The Dirty Life certainly isn't the first reverse Cinderella story to be published, Kimball's prose elevates it to the exemplary. Her musings on the brutal acclimatization to agricultural life are deeply honest: she reveals rash anger, deep frustrations, ample failures and even her own prejudices ("there's no better cure for snobbery than a good ass kicking").

At many turns she expresses remorse for the old life she sacrificed in exchange for the new life that's manifesting in fits and starts. And yet there are those magical, only-on-the-farm moments that buoy her up and eventually tip the balance in favor of her new chapter. One passage about a newborn cow has stuck with me in the 6 years since I first read it:

I stopped to inspect the calf, who was curled into the straw ... She unfolded her front legs cautiously, one at a time, and wobbled there. Her focus seemed to shift between this new world and the quiet within. She was still only tenuously connected to our side, to light and time, air and gravity. At births, I find that it's this, and not the slip and splash of delivery, that gives us a glimpse of mystery. Newly born creatures carry the great calm of the Before with them, for minutes or hours, and when you are close to it, you can feel it, too.

It's a gorgeous and heartfelt story that broadened my horizons and inspired new ways of thinking.

From its brilliantly punny title, Josh Kilmer-Purcell (whom we interviewed in 2014) prepares his readers for the wild and hilarious ride that awaits them when they open the cover of The Bucolic Plague. The story recounts the (mis-)adventures of Manhattanites Kilmer-Purcell, an advertising executive and sometime drag queen, and his now-husband Brent Ridge, a doctor who featured prominently in Martha Stewart's television show and publications, as they restore a historic 1802 estate and farm in Sharon Springs, N.Y. They since have experienced wild success — in the form of a television show, published cookbooks, brick-and-mortar stores, and collaborations with Target, Bed Bath & Beyond, and Andaz Hotels — but the early days were rough going. Kilmer-Purcell writes with skillful humor that brings to mind David Sedaris, describes painful moments with great poignancy and depicts the process of entrepreneurship in terms that ran true.

The stories of these writers-cum-farmers are essential reads. While they detail very different paths, they each inspire the reader to explore and embrace new undertakings, to question their paradigms, and to find the boundless beauty that's found throughout New York State. Both authors also emphasize the impossibility of their success without the generous assistance of their neighbors. It's a hopeful reminder in these days of division throughout our country.

Leave a comment